Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH)

Understanding PNH infographic

Understanding PNH

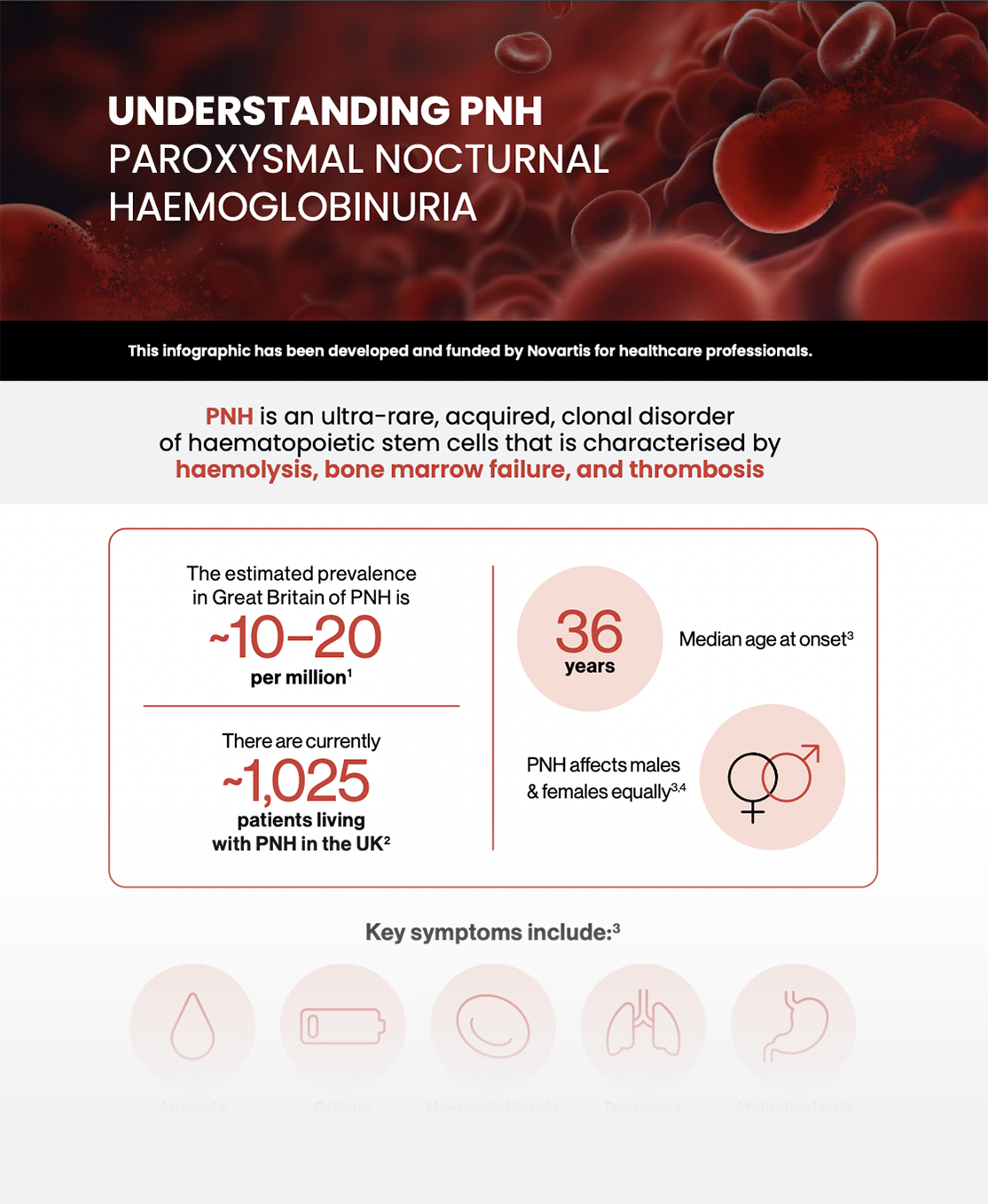

PNH is an ultra-rare, acquired, clonal disorder of haematopoietic stem cells that is characterised by haemolysis, bone marrow failure, and thrombosis.

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) is a chronic, life-threatening, ultra-rare blood disorder that often manifests with complement-mediated haemolysis, anaemia, and fatigue.1 In PNH, red blood cells (RBCs) are destroyed prematurely by the complement system, leading to a range of potentially debilitating symptoms.

PNH occurs due to an acquired mutation in the body’s haematopoietic stem cells, which makes the RBCs more susceptible to haemolysis by the complement immune system.2,3

The estimated prevalence in Great Britain of PNH is ~10 to 20 per million4 Currently ~1,025 patients are living with PNH in the UK5

median age at onset:

36 years6

PNH equally affects

males and females6,7

PNH varies in presentation and is often associated with other clinical conditions, such as aplastic anaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.7

Although the name of the condition refers to nocturnal haemoglobinuria, resulting in the production of classically dark urine during the night and in the morning, this symptom is intermittent and usually only present in approximately 25% of patients.4

Key signs and symptoms6

Signs and symptoms observed in the international PNH Registry, an ongoing, prospective, multicentre, global, observational study. Current analysis includes patients enrolled in the Registry who had data available as of July 17, 2017.6

Anaemia

9.8 g/dL

Median haemoglobin level

Fatigue

81%

(n=2684/3318)

Haemoglobinuria

45%

(n=1492/3313)

Dyspnoea

45%

(n=1501/3315)

Abdominal pain

35%

(n=1167/3314)

Erectile dysfunction

24%

(n=344/1422 males)

Dysphagia

17%

(n=547/3311)

Thrombosis

13%

(n=544/4134)

Symptom burden typically results in patients with PNH having lower quality of life (QoL) compared with the general population6

Complications6

19%

of patients have a history of major adverse vascular events

61%

have a history of RBC transfusions

43%

show some level of renal impairment

Thrombotic events are the leading cause of mortality in PNH, accounting for up to 67% of deaths with a known cause8

In its most severe form, PNH may lead to chronic anaemia, which can result in patients becoming transfusion-dependent, requiring patients to adapt their lives around scheduling treatment. Iron overload can also be a complication of chronic transfusions and can increase morbidity and mortality.9

Patients can also suffer from the direct effects of intravascular haemolysis leading to the absorption of nitric oxide. Nitric oxide is a major regulator of vascular physiology and many clinical symptoms seen in PNH are caused by depletion of nitric oxide, such as thrombosis, fatigue, abdominal pain, oesophageal spasm, and male erectile dysfunction.8,10

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of PNH may be suspected in individuals who have signs of intravascular haemolysis (e.g., haemoglobinuria, abnormally high serum LDH concentration) with no known cause.4,7

A diagnosis may be made based upon a thorough clinical evaluation, a detailed patient history and a variety of specialised tests, including:11,12

Abdominal ultrasound

Bone marrow examination

CT scan

D-dimer

Echocardiogram

Full blood count

Kidney function test

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

Reticulocyte count

Bilirubin levels

Diagnosis of PNH is confirmed by flow cytometry, which is regarded as the gold standard test for diagnosis7

Flow cytometry is used to detect GPI-linked antigen deficiency in red cells, monocytes and granulocytes.7

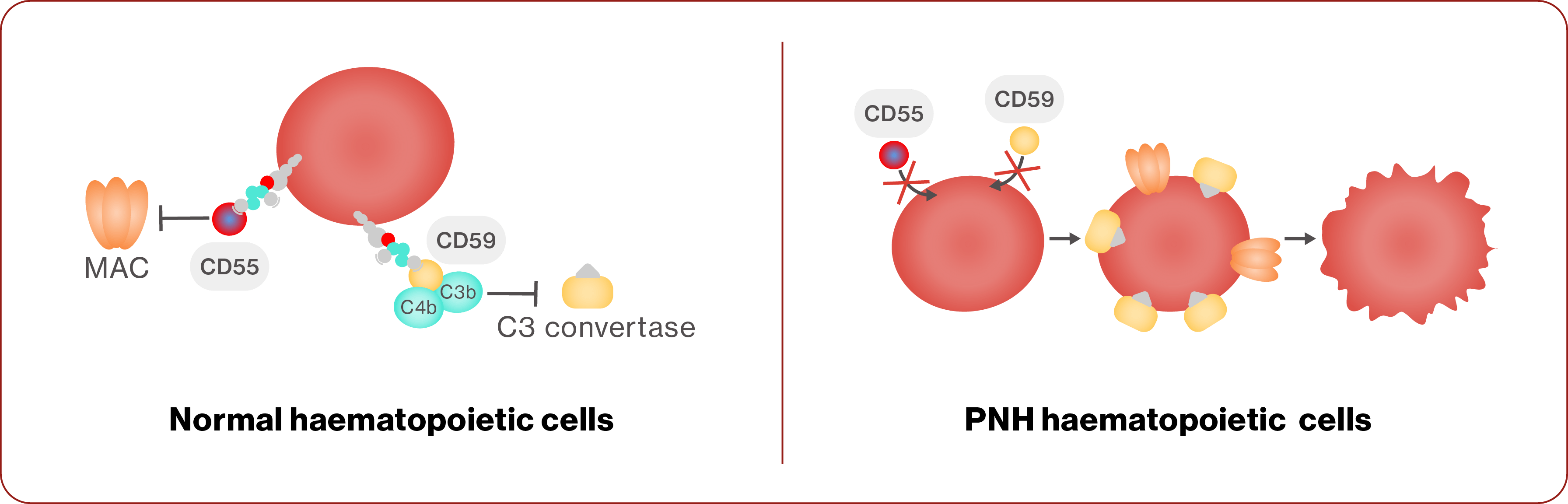

Mechanism of disease

PNH develops due to a mutation in the PIG-A gene, which is necessary for the creation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors on the cell surface that attach proteins, including CD55 and CD594,13

CD55 and CD59 normally prevent the complement system from destroying normal cells, and in PNH, loss of the GPI anchor results in the lack of CD55 and CD59 on cells13

This leads to complement-mediated haemolysis4,13

Management goals

PNH treatment aims to address specific symptoms that are present in each individual and includes a variety of different therapeutic options.7

Approved therapies are not curative, but work to inhibit components of the complement system, halting the destruction of RBCs and can reduce the risk of thrombosis.7

The only curative therapy for individuals with PNH is bone marrow transplantation. However, because of the risk of morbidity and mortality, this is reserved for individuals with serious complications such as severe bone marrow failure or repeated, life-threatening blood clot formation.7

Additional treatment for PNH is symptomatic and supportive and varies depending upon the individual’s age, general health, presence of associated disorders, severity of PNH and degree of underlying bone marrow failure.7

MAC, membrane attack complex; PIG-A, phosphatidylinositol glycan, class A.

References

Dingli D, et al. Ann Hematol 2022;101(2):251–263.

Cançado RD, et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther 2021;43(3):341–348.

Risitano AM, et al. Blood 2009;113(17):4094–4100.

Orpha.net (2024). Parmoxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/447?name=&mode=name. [Accessed October 2024].

The National PNH Service (2024). Annual Report. Available at: https://pnhserviceuk.co.uk/healthcare-professionals/annual-report/. [Accessed October 2024].

Schrezenmeier H, et al. Annals of Hematology 2020;99:1505–1514.

National Organization for Rare Disorders (2024). Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/paroxysmal-nocturnal-hemoglobinuria/. [Accessed October 2024].

Hill A, et al. Blood 2013;121(25):4985–4997.

Bektas M, et al. JMCP 2020;26(12).

Brodsky RA. Blood Rev 2008;22(2):65–74.

PNH Support (2024). Diagnosis. Available at: https://pnhuk.org/what-is-pnh/diagnosis/. [Accessed October 2024].

EMBT (2015). Understanding PNH. Available at: https://www.ebmt.org/sites/default/files/migration_legacy_files/document/EBMT%20Practical%20Guides%20for%20Nurses_Paroxysmal%20Nocturnal%20Haemaglobinuria%20%28PNH%29_UK.pdf. [Accessed October 2024].

Brodsky RA. Blood 2014; 124(18):2804–2811.

UK | October 2024 | FA-11214740

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard. Adverse events should also be reported to Novartis online through the pharmacovigilance intake (PVI) tool at www.novartis.com/report, or alternatively email [email protected] or call 01276 698370.